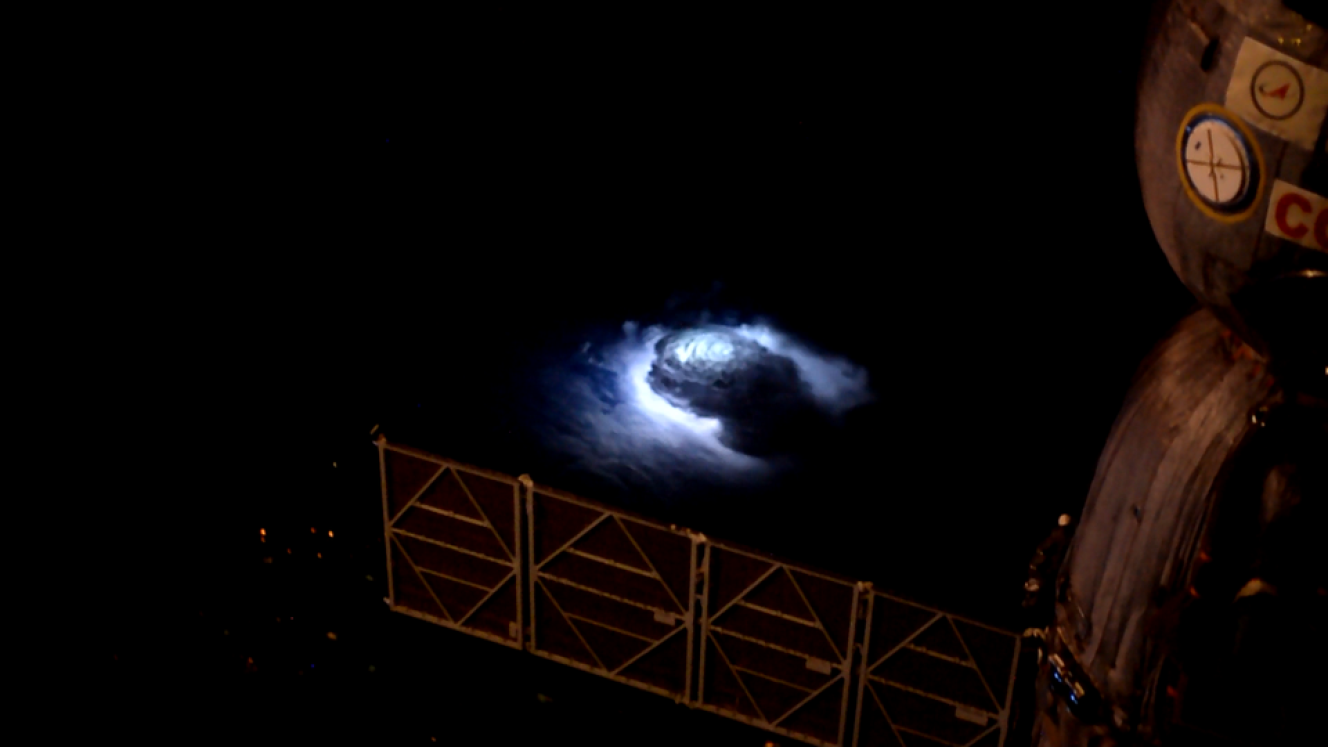

High above storm clouds and far beyond the reach of commercial aircraft, scientists are studying elusive electrical discharges known as transient luminous events (TLEs). These short-lived phenomena include red sprites, blue jets and ELVES: bursts of light triggered by lightning that occur tens of kilometres above active thunderstorms.

For decades, pilots reported unexplained flashes in the upper atmosphere. Researchers later confirmed these sightings and coined names for the different forms they observed. Today, those reports are being matched with hard data thanks to the Atmosphere–Space Interactions Monitor (ASIM), which has been operating aboard the International Space Station since 2018.

Developed by Danish aerospace firm Terma and operated from a control centre in Belgium, ASIM was designed to detect visible light, ultraviolet radiation and X-rays produced by rare electrical activity between 20 and 100 kilometres above Earth’s surface. Mounted externally on the station, it has a clear view of large thunderstorm systems, particularly over equatorial regions where lightning activity is most intense.

ASIM’s high-speed photometers and X-ray sensors capture fleeting events such as ELVES and red sprites, which appear as vertical structures often described as "jellyfish-like" in shape. These discharges last only milliseconds, but they release vast amounts of electromagnetic energy.

One of ASIM’s key findings is that lightning-related discharges can propagate energy all the way to the ionosphere, the charged layer of the atmosphere that enables long-distance radio communication. These vertical energy pulses may influence how radio signals travel across continents, with potential implications for aviation, maritime navigation and military communications.

Orbiting roughly 400 kilometres above Earth on Europe’s Columbus laboratory module, ASIM continuously monitors storm systems as the station passes overhead. According to Torsten Neubert, the mission's lead scientist, the instrument has exceeded expectations. “We are seeing far more activity above cloud tops than previously assumed,” he says, “and these processes may play a role in how storms interact with the wider atmosphere.”

From orbit, astronauts and instruments alike are now observing thunderstorms as vertically connected systems rather than isolated weather events. The growing body of data suggests that the energy generated by storms frequently travels well beyond the visible cloud layer, opening new lines of inquiry into atmospheric dynamics, space-weather interactions and the hidden electrical complexity of Earth’s storms.