Matt Feinstein, CEO of LNX Solutions, suggests that it may be time to turn back the clock to achieve true data sovereignty.

Global technological interdependence accelerates innovation by creating large-scale collaboration networks. Innovators can develop new technologies more quickly and the result is faster innovation and increased economic efficiency.

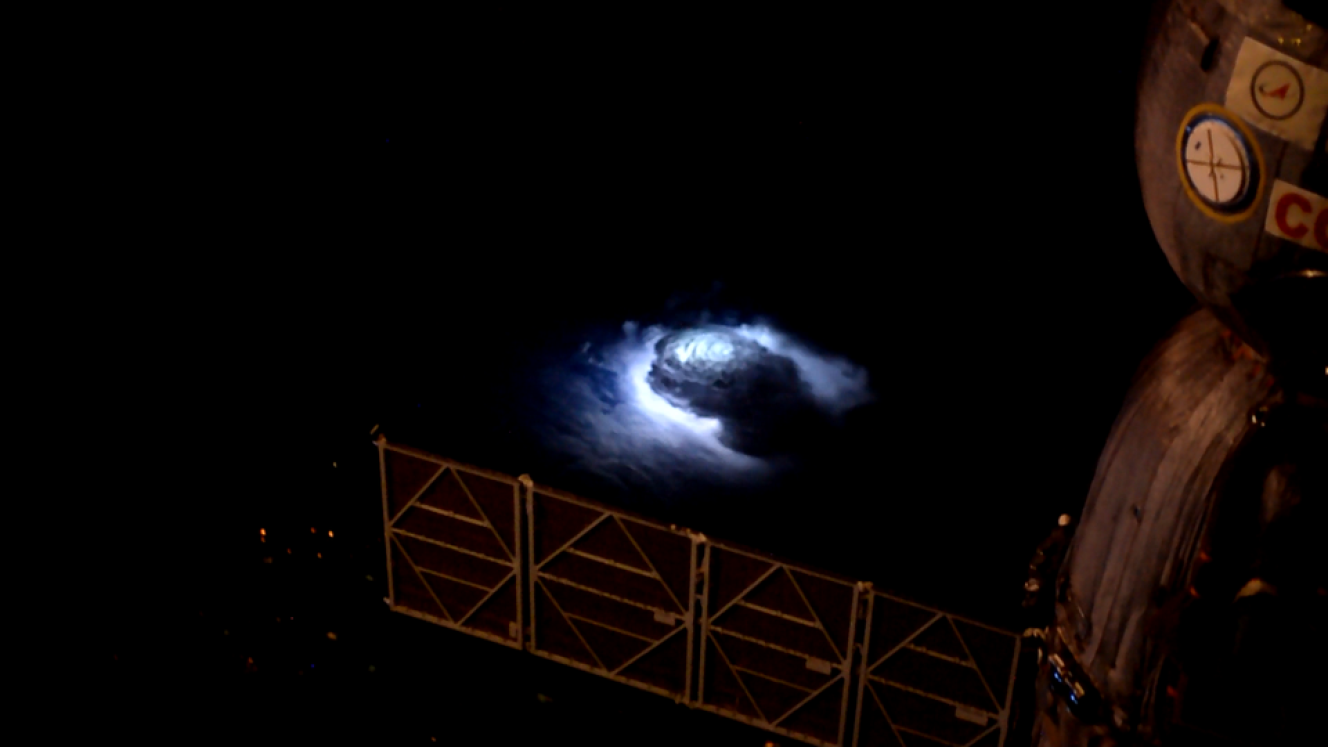

Unfortunately, the downside of the interconnected nature of technology, which enables countries and companies to build on each other's advancements, can be as severe and disruptive as the natural events that have devastated the Caribbean this past week.

Indeed, before Hurricane Melissa left a trail of devastation in Jamaica and Cuba earlier this month, we could say Hurricane Amazon affected thousands of companies and caused widespread disruption over an even greater area. Social media, gaming, banking, entertainment and many other categories of platforms went down almost everywhere and the chaos persisted as much of the planet tried to reboot their AWS services pretty much simultaneously.

This Amazon Web Services “e-Hurricane” event that caused such global chaos originated from an internal Domain Name System (DNS) failure within the biggest AWS data centre region in the United States.

While the details of this outage and what man-made disrupting events were triggered are not really important here, the takeaway that is vitally important is this: As global technological interdependence emerges as a serious risk for South African businesses, we can take a page from 1986 — a time when international sanctions compelled local industries to build resilience and self-reliance under immense pressure.

In the 1980s, South Africa was required to become self-sufficient to survive. Setting aside the reasons for all of this, corporate South Africa needs to relearn some sanctions-busting lessons to survive the regular fallout from over-dependence on IT services most often emanating from a handful of Silicon Valley-based vendors.

Yes, it's a digitally-connected world, but the risk of having all of one's eggs in one basket remains a truism for the ages.

So what to do? South African organisations must embark on a quest for data sovereignty with an urgency like its 1986. Broadly speaking, we must continue to use the world's best cloud and computing services offered by the world's best companies like Amazon and Microsoft.

However, we need to recognise that protecting our national interests - and business efficiency - means taking proactive measures to ensure that South African organisations always have full access and control over South Africans' data. How can it be acceptable for South Africans not to be able to access their own data and services because a server went down on America's east coast?

Most of South Africa’s data resides in hyperscale data centres owned by the United States, and now China, and there has lately been recognition of data being a national asset and even talk of a South African state-owned hyperscale data centre with the same capacity and performance as Azure, AWS, Huawei Cloud, and Google Cloud.

Building state-owned data centres is an overly simplistic, somewhat pie-in-the-sky approach. It doesn't recognise that data sovereignty is a complex legal and technical concept that requires a holistic approach. This would include enacting robust laws and strong security protocols over the long term.

What local firms can do right now to boost data sovereignty at little cost is to insist on using domestic colocation providers that offer rack space within SA-based data centres. By doing this, South Africa will immediately gain greater control over where its data is physically located, and this is a critical first step toward true eventual data sovereignty.

Domestic colocation providers ensure data residency, making one's data subject to South Africa's rules and regulations.

In addition, co-location facilities offer strong physical security, and using a local provider can build trust among citizens and businesses.

Finally, data stored in a domestic facility is less likely to be subject to the extra-territorial access laws of other countries, such as the US Cloud Act.